The role of a school administrator continues to expand and intensify leaving many to focus less on self-efficacy as an instructional leader leading to decreased dissatisfaction in the role.

Recent studies released from the Alberta Teacher’s Association (2019, 2021) highlight the growing issues for school leaders including increased instances of compassion fatigue and moral distress (Alberta Teachers Association, 2021). McRae (2022) highlighted the overwhelming frustration and hopelessness expressed by administrators in Alberta as well as a growing concern of the number of teachers who are choosing not to go into leadership roles for the same reasons. There needs to be opportunities for school leaders to do their work differently and to “create new spaces for recovery; reminding ourselves that hope is bound in heart, mind and will.”

Who We Are

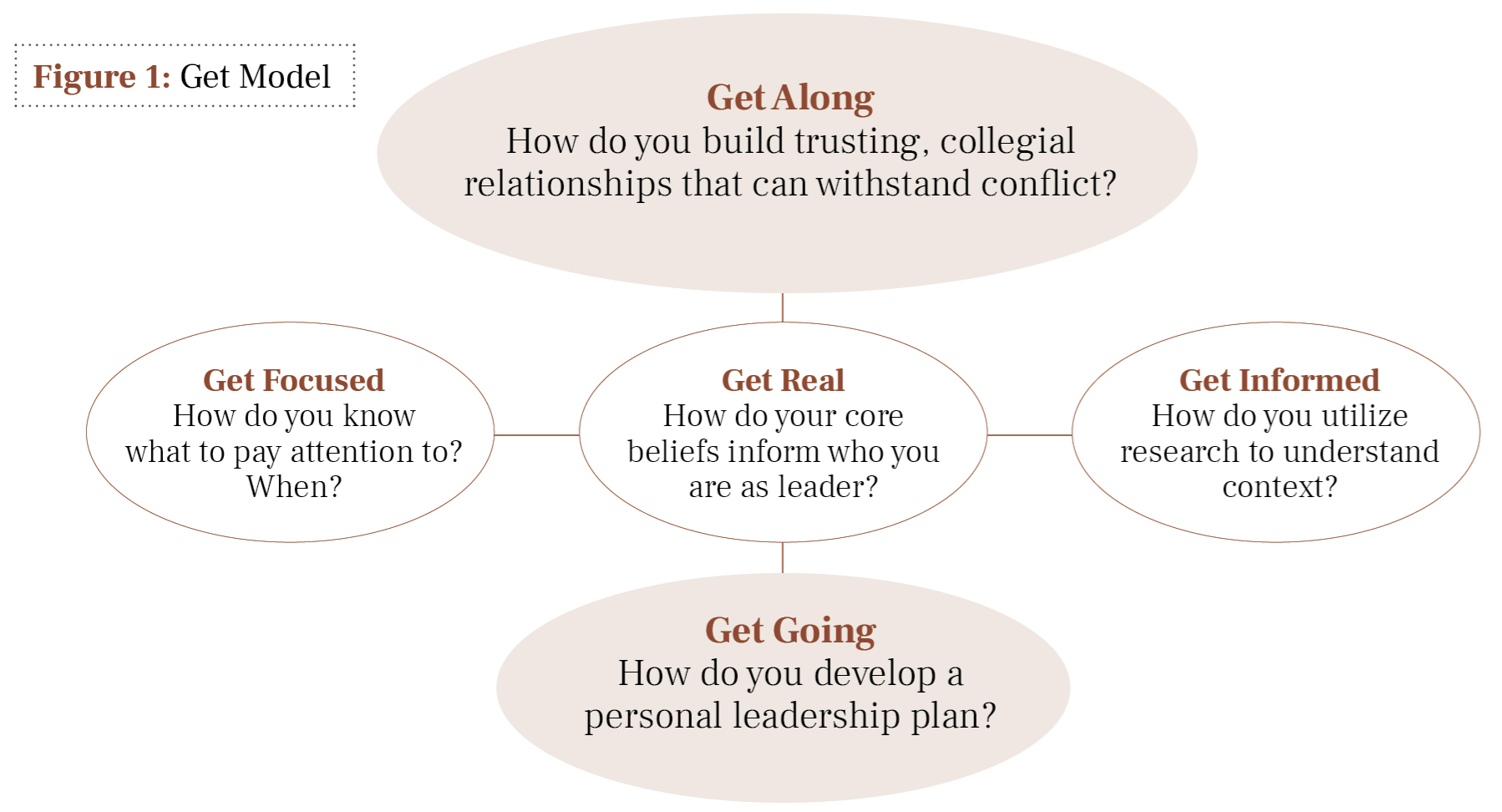

The School of Education at Ambrose University offers a provincially mandated certification program for new school leaders that is focused on transformational leadership through a foundation of personal development, based on our GET leadership model (Figure 1) (Martens et al., 2018). Participants are asked to develop a personal vision of leadership through guided inquiry, case studies, and journaling based on each “GET”. Throughout two, asynchronous, on-line courses, they reflect and question personal beliefs about leadership through a focus on research and best practices about transformative leadership, interwoven with personal reflection and narrative. Participants were also asked to not only complete the asynchronous discussions bi-weekly but encouraged to participate in informal synchronous conversations. These “Coffee and Conversation” sessions allowed for open collaborative engagement with one another, and we began to see how participants were taking up their work personally and supportively with peers.

Noddings (1982) described an ‘ethic of care’ as a “state of being in relation to and characterized by receptivity, relatedness and engrossment” (p. 5) and as such, an ‘ethic of care’ as imagined by Noddings has rarely been applied to a school leadership context. As both instructors and participants in these informal conversations, we began to see how these open conversations began to emerge as a community of caring, described by Noddings. These conversations were welcomed by our participants, to share and unpack what they were encountering in their new roles which was different from the professional development they were engaged in with their school districts. While there are professional learning opportunities for school leaders, they are often focused on learning models that are transferable to school-based outcomes and leading teacher learning (Day & Dragoni, 2015; Mendels & Mitgang, 2013).

This can lead to an increased sense of isolation and the inability to reach out for support from other school leaders. We see a gap in educational research that explores the need for ongoing professional learning opportunities for school leaders that allow for trusting, open conversations that build an ‘ethic of care’ community with peers and mentors that is focused on personal development. Our research seeks to understand how the creation and participation in an ‘ethic of care’ community contributes or supports school leaders to flourish within a rising context of moral distress and compassion fatigue.

Our Study Through Story

“We exist in a bundle of life. We say, ‘A person is a person through other people.’ It is not, ‘I think therefore I am [but rather] I am human because I belong. I participate, I share” (Tutu, date, as cited in Wheatley, 2017, p. 223).

We considered the many course participants, school leaders from multiple public, independent, and international schools, in a mandatory professional certification program that was focused on transformational and servant leadership founded on personal and spiritual beliefs. Using narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) as a research methodology, we sought to understand the lived experience of these newly appointed or emerging school leaders through the telling of their stories. These stories are not just isolated events but rather, together, form an understanding of how school leaders experience their professional and personal learning journeys. Conversations were framed through several questions centered on an exploration of understanding self, others, and contexts in critical, caring conversations with each other, and the course instructors. We began with a survey to understand why, if, and how the informal conversations were contributing to their growth as leaders as illustrated by the following responses:

“It was helpful to connect with the group, to hear how they were applying the learning of LQS in their practice. As my scope is pre-service teachers and field experience, I was completing this without being connected to a K-12 school division. I appreciated hearing from others and contributing to the coffee conversations!”

“I found it most informative to hear the experiences of my colleagues. It was an opportunity to listen to new ideas, pose potential solutions, and continue to evolve my leadership practice as required under LQS. Furthermore, as I was relatively new to administration at the time I found it very beneficial to listen to the insights of my more experienced colleagues.”

“I find it interesting to listen to peers in Alberta talk about success and struggles that are similar to what I see. It is great PD, and it aligns with many LQS strands in my current PGP”.

Following the survey, we interviewed participants to develop a deeper understanding of these informal conversations and why, if and how they were contributing to their growth as leaders. Aria, a pseudonym, noted that coffee conversations offered a relaxed atmosphere to personally connect in an online space. Aria pointed out that leaders and teachers are struggling and that opportunities such as coffee and conversation to personally connect and share the struggles they are faced with and listen to how others are working through these challenges is valuable and needed.

Sam (pseudonym) shared about the value of coffee conversations in fostering hope for school leaders. Hope emerged from coffee conversations as different perspectives and ideas were shared around the struggles people shared during these informal gatherings. Sam also spoke of how these conversations were ones that might not have been started at their workplace but here at the coffee chats they were possible; possible because “maybe they don’t want to talk to somebody at work about it”. These conversations brought hope in these situations because now there was someone to talk to about struggles and ways to get ideas for how a problem could be solved.

The participants valued the opportunity to be in community with others who were just beginning in their roles as well as more experienced. It is interesting that they felt the differing voices from the variety of school districts added to their growth, perhaps because they could speak to leadership more globally rather than be caught up in managerial routines or policies specific to their workplaces. This was particularly true when they encountered competencies related to Leadership Quality Standard (LQS) 5, “A leader supports the school community in acquiring and applying foundational knowledge about First Nations, Métis and Inuit for the benefit of all students” (Alberta Education, 2020), as well as emerging issues that they encountered, which had been highlighted in the course are seen in the following survey responses:

“I appreciated the opportunities to connect and the Indigenous Foundational Knowledge sessions.”

“How to respond to the changing landscape of education as we shifted from in-person to online learning. Dealing with challenges (competency vs compliance) that arrive as a supervisor when dealing with instructional and support staff. Balancing the initiatives from the school district without contributing to staff burnout. Managing the changing climate when it comes to issues of social justice.”

Conversations that foster generative dialogue and are based in trust and empathy have been shown to be an integral part of leadership development (Allan et al., 2021; Adams et al., 2021). We would suggest, based on the participant’s input, that they are often reluctant to disclose issues they are encountering with supervisors, for fear that they will not look competent. This was evident in our interviews with the participants.

Jerome, a pseudonym, shared his experiences with coffee conversations and how this was an uplifting and comfortable environment where one could debrief with others in a place that was free from regulation, supervision, and evaluation. This was a place where he could be open and honest about struggles: “I knew that this was a place where there was no judgments; people were going through a variety of different challenges, regardless of their context as an administrator”. Jerome used the word “uplifting” to describe these coffee conversations and said that the “most uplifting part is that I could speak openly and honestly and say some things that I felt needed to be said, without the cloak of maybe a supervisor or something along those lines”. He noted further that this “created a place of empathy really among strangers, but that we knew we were going through similar experiences” and “the joy and laughter and humor in things that was very comforting for me”. Henry, a pseudonym, added, “I feel less isolated and understand that I am not the only one who is going through professional challenges that impact my personal life. It helped me to gain insight, ideas, and strategies for dealing with a variety of situations”.

Supporting the Changing Roles of School Leaders

“You cannot build on broken…It’s the recipe for building healthy communities. When you strengthen connections, even among those who have been indifferent or hostile, you create possibilities. We may be strangers or estranged, but we can become neighbors if we decide to work together on building something good. For good. We are not broken people. It’s our relationships that need repair. It’s relationships that bring us back to health, wholeness, holiness” (Wheatley, 2017, p. 239-240).

We have undergone incredible disruption over the past few years that has contributed to already-growing issues for school leaders including compassion fatigue, moral distress, and an increased concern in personal well-being (Alberta Teachers Association, 2021). School districts must consider how school leaders are supported to thrive, personally, if they want to attract and retain individuals who do this work. They also should consider moving beyond offering professional learning opportunities that are focused on performance-based outcomes linked to student and teacher learning and consider a focus on leaders’ sense of self, mental health and well-being (Day & Dragoni, 2015; Mendels & Mitgang, 2013)

through generative dialogue and collaborative inquiry (Adams et al., 2021) and build an ethic of care community. This research reveals an important aspect of leadership development that is absent from professional learning for school leaders that can lead to their ability to feel and be more effective in their roles.

School superintendents can re-imagine ‘support’ for leaders to include collaborative networks that are broader in membership than just their district. New and emerging leaders find it beneficial to connect with those who are not part of the supervisory process and open dialogue built through trusting relationships, can lead to higher degrees of effectiveness and personal well-being. This may also lead to a greater ability to flourish as a school leader and allow for stronger relationships with colleagues and staff members to grow.

ReferencesAdams, Braunberger, D., Hamilton, S., & Caldwell, B. (2021). Leaders in Limbo: The Role of Collaborative Inquiry Influencing School Leaders’ Levels of Efficacy. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 22(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v22i1.551

Alberta Education. (2020). Leadership quality standard. https://www.alberta.ca/assets/documents/ed-leadership-quality-standard-english.pdf

Alberta Teachers Association. (2019). Alberta School Leadership Within the Teaching Profession 2019: Seismic Shifts and Fault Lines: Experiencing the Highs, Lows and Shadows. https://legacy.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/COOR-101-26%20School%20Leadership%20in%20the%20Teaching%20Profession.pdf

Alberta Teachers Association. (2020). Compassion Fatigue, Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout: Research Study. https://legacy.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/COOR-101-30%20Compassion%20Fatigue%20Study.pdf

Allan, Adams, & Momborquette. (2021). Critical Conversations to Enhance Leaders’ Perceptions of Professional Efficacy. In B. Kutsyuruba, S. Cherkowski and K.

Walker (Eds.), Leadership for Flourishing in Educational Contexts. (pp.145-162). Ontario: Canadian Scholars. Clandinin, D. J. & Connelly, D. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Day, D. V., & Dragoni, L. (2015). Leadership Development: An Outcome-Oriented Review Based on Time and Levels of Analyses. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111328

McRae, P.(2022, April 10-12). Principals of Pandemic Recovery: Creating New Spaces for Hope and Resilience. [Keynote] uLead 2022: The Summit of Educational Leadership. Banff, Alberta.

Mendels, P., & Mitgang, L. D. (2013). Creating strong principals. Educational Leadership, (April), 22–29. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rch&AN=86921385&site=ehost-live

Noddings, N. (1982). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral Education. Berkeley: University of CA Press.

Noddings, N. (2002). Educating moral people: A caring alternative to character education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Wheatley, M. (2017). Who Do We Choose to Be? Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity (1st ed.). Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

AUTHOR BIOS:

Dr. Sherry Martens has served as a classroom teacher, system specialist, school-based administrator in Alberta schools since 1987. She is currently the Associate Dean and Assistant Professor in the School of Education and Adjunct Professor in the Graduate Division of Educational Leadership at Gonzaga University. Her research explores the identity formation of teacher and school-based leaders, curriculum theory, and decolonizing teacher education spaces.

Dr. Christy Thomas is an Assistant Professor in the School of Education at Ambrose University and an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Werklund School of Education. Christy’s research centers on leadership, professional learning, and collaboration which is fueled by her desire to build communities of practice that support flourishing for all.